|

|

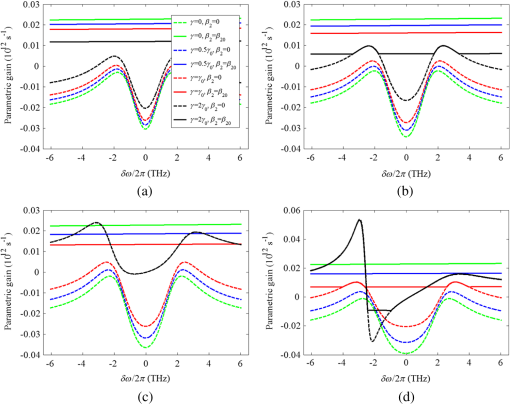

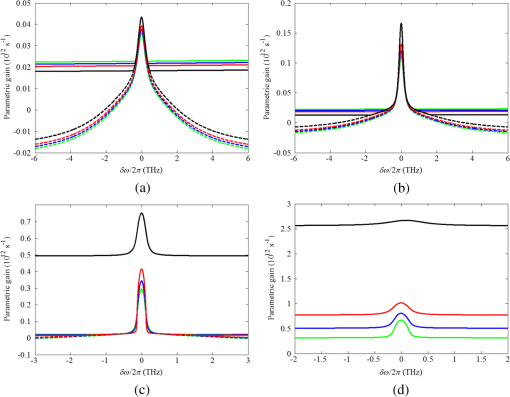

1.IntroductionStability of pulse generation from midinfrared (MIR) quantum-cascade lasers (QCLs)1,2 has been an active field of research owing to the fact that stable MIR pulses are desired for free-space communication, medical diagnosis, and environmental sensing applications,3 and QCLs are important sources for such pulses. However, a full picture of stability analysis of QCLs is inevitably complicated when compared to conventional lasers because of the unique combination of ultrafast carrier scatterings and gain recovery,4–6 significant nonlinearities,7 and dispersion effect8 in a QCL medium. There have been several discussions on the stability of typical MIR QCLs both theoretically and experimentally;9–12 however, none of these discussions specifically addresses the effect from group-velocity dispersion (GVD). In Ref. 9, observations of the coherent Risken–Nummedal–Graham–Haken (RNGH)-like13,14 multimode instability in QCLs have been reported. It is found that the instability threshold is significantly lower than that of the original RNGH instability, which is attributed to the saturable absorber effect in the lasing medium. Thereafter, more comprehensive theoretical and experimental investigations on the multimode operation regimes in QCLs have been documented in Ref. 10. It is shown that the fast gain recovery of QCLs exhibits two kinds of instabilities: one is associated with the spatial hole burning (SHB) effect and the other is RNGH-like instability. The QCLs’ stability analysis is based on the linearization of the Maxwell–Bloch formalism. The RNGH instability of QCLs exhibits two differences from that of the conventional RNGH instability, namely, lower instability threshold and missing of the central spike in the optical spectrum. According to the analysis reported in Ref. 10, the first difference is owing to the presence of a saturable absorber effect in the QCL cavity and the second difference is owing to the SHB effect. The saturable absorber effect originates from the Kerr nonlinearity15 in QCLs, and it is also called the transverse Kerr effect. Accompanying the saturable absorber effect, there is the longitudinal Kerr effect, which induces self-phase-modulation (SPM) of lasers. A discussion of the effect of SPM on the QCLs’ instability is reported in Ref. 11, where it is found that the SPM could significantly broaden the unstable domain of the RNGH instability but it only has a trivial effect on the instability threshold. Moreover, the instability of the QCLs is viewed at a different angle,12 where the instability mechanisms are decoupled into the amplitude and phase domains based on the symmetry and antisymmetry of the propagating fields in the lasing cavity. The amplitude instability is of the RNGH-type multimode instability and the phase instability is of a single-mode nature. Both saturable absorber and SPM effects are accounted for in the analysis. The saturable absorber effect could lower the threshold of both amplitude and phase instabilities, while the SPM effect could broaden the frequency domain of both instabilities. Similar to the Kerr nonlinearity, the GVD also originates from the intersubband transitions of the QCLs and it is embedded in the same structure as that of the Kerr nonlinearity. However, so far, its interaction with either saturable absorber or SPM has never been accounted for in the stability analysis of a typical QCL structure. A measurement of GVD in the MIR QCLs has been reported in Ref. 8. An ultrafast upconversion technique based on the sum-frequency generation was applied to investigate the total GVD by measuring the wavelength-dependent pulse propagation delay.8 The measurement on a QCL with an InGaAs/InAlAs active region shows an anomalous GVD with the coefficient of .8 It is stated in Ref. 16 that the low GVD of the QCLs tends to lock the longitudinal modes of the QCL designed for the MIR frequency comb. The interaction between the GVD and the saturable absorber in the self-induced transparency (SIT) modelocking of QCLs is discussed in Ref. 17, where analysis based on the pulse shape evolution demonstrates that the stability limits for saturable gain and saturable loss with the presence of GVD depends on the ratio of the SIT-induced gain and absorption to the linear loss. In our current work, we focus our discussion on the effect of the GVD on the stability of a typical MIR QCL without the mode-locking mechanism. The novelty of this paper is in the inclusion of the GVD effect in the analysis of instability mechanisms of MIR QCLs. We particularly investigate the interaction between the GVD and the saturable absorber on the QCL stability. At this point, we have not involved the SPM effect, as we are planning to take it in our next work. These works are toward our goal of investigating the possibility of forming an optical soliton in the QCLs for MIR pulse generation. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sec. 2, the linearization of nonlinear Maxwell–Bloch equations with the GVD effect and the decoupling of amplitude and phase stability mechanisms is described. Section 3 presents the solution to quadratic eigenvalue problems that result from the GVD effect in the amplitude and phase stability analysis. In Sec. 4, results are presented and discussed. Conclusions are drawn in Sec. 5. 2.Linear Stability Analysis with Second-Order GVDThe dynamic behavior of QCLs is modeled based on the two-level Maxwell–Bloch formalism. The QCL gain medium is assumed to be built with the Fabry–Perot cavity, thus, the SHB effect, brought by the standing waves, are accounted in the model. Both the second-order GVD and saturable absorber effects are included as well. We have the Maxwell–Bloch equations as where , , , and are the variables that govern the dynamics of lasing system, and are the envelopes of the normalized electric field and polarization, respectively, subscript represents the forward (backward) propagation of waves, is the normalized average population inversion and is the population inversion grating, which accounts for the SHB effect,8 is the steady-state normalized population inversion proportional to the pumping factor (), and are the longitudinal and transverse relaxation times, respectively, is the parameter that describes the strength of the SHB and it ranges from 0 (no SHB) to (the strongest SHB), is the linear cavity loss; , where is the coefficient that describes the strength of the saturable absorber and is the transition dipole moment, and the parameter is the GVD coefficient.The linearization of the dynamic Eqs. (1)–(6) is achieved through the addition of a small perturbation to the steady-state solution. Then, a set of equations with respect to the perturbations are obtained as Without loss of generality, we assumed that all the variables are complex numbers except the population inversion . The steady-state solution for Eqs. (1–6) is obtained as where .In order to decouple the behaviors of these variables into amplitude and phase domains, we adopt the polar expression for each variable, i.e., , where is any of the variables in Eqs. (1–6). Through some mathematical manipulations, the small perturbation is expressed in the polar form as where is the steady-state solution. In detail, we take the following notations for the polar expression of each variableBringing Eqs. (17) and (18–21) into the differential equations in Eqs. (7–12) of the perturbations, the perturbations in amplitude and phase are decoupled into two equation sets as andEquations (22–27) describe the amplitude perturbations, while Eqs. (28–32) are phase perturbations. Owing to the symmetry and antisymmetry relationships between each pair of forward and backward propagating variables, such as , , , and , the number of equations involved in the stability analysis can be reduced. In the Fabry–Perot cavity , the symmetry and antisymmetry relationships about the cavity center are expressed as From Eqs. (22–27) and (28–32), it can be found that the pairs and possess symmetry about the cavity center and the pairs and possess antisymmetry about the cavity center. Subsequently, those two sets of equations are reduced to Eqs. (35–38) and (39–41), respectively, andThe amplitude stability analysis is based on Eqs. (35–38), while phase stability analysis is based on Eqs. (39–41). Both equation sets involve a second-order differential term that is brought by the GVD effect, which results in the quadratic eigenvalue problem in the stability analysis. 3.Stability Analysis Through the Quadratic Eigenvalue ProblemDynamic behaviors of amplitude and phase are described by equation sets (35–38) and (39–41), respectively. Examination of stability is conducted by solving the eigenvalues for each equation set. In this case, we need to deal with the quadratic eigenvalue problem that results from the GVD effect. We take equation set (35–38) for amplitude stability as the example to illustrate our solution procedure for the quadratic eigenvalue problem. We consider transforming the second-order differential equation to a first-order differential equation; thus, the quadratic eigenvalue problem will be degenerated to a linear eigenvalue problem that we are familiar with. For equation set (35–38), by defining an additional variable, , the second-order differential equation set (35–38) is linearized (or reduced to the first-order differential equation) in the matrix form as The stability of the dynamic equation set (35–38) is studied by finding the eigenvalues of the matrix in Eq. (42). Assume that is any of the eigenvalues and with some mathematical manipulations based on Eq. (42), we arrive at where Thus, for field at the two boundaries of the cavity, there isThe value for can be figured out from the boundary conditions of the Fabry–Perot cavity. As the mirror reflection at the two facets has been accounted for in the linear loss in Eqs. (1) and (2), the boundary conditions become formally identical to those ideal Fabry–Perot resonators with perfectly reflecting mirrors, i.e., and . Combining these boundary conditions with the symmetry relationship between the forward and backward propagations stated in Eq. (33), we have , and then, After substituting Eq. (46) into Eq. (45), we get the transcendental equation for the entire spectrum of eigenvalues as where is any integer number, i.e., .The stability of dynamic behaviors in the amplitude described in Eq. (42) is characterized by the eigenvalues . Each integer number represents a transverse wave mode with an offset frequency of from the central frequency , and , where it implies that the separation between the two adjacent wave modes is the round trip frequency along the cavity. For each mode, if the maximum real part of all the eigenvalues (the parametric gain) is negative, then the mode is stable; otherwise, the system is unstable when the parametric gain is positive or the system is marginally stable with zero parametric gain. We follow a similar procedure to analyze phase stability. To avoid redundancy, here, we only present the major steps in the derivation procedure. The linearized dynamic equation for the phase domain based on Eqs. (39–41) is With any eigenvalue of the above matrix, we have the following relationship about the phase angle of the electric field at the two boundaries of the cavity, whereThe above transcendental equation is solved by incorporating the boundary conditions of the phase angle. The following relationship holds because of the reflection of the phase angle at each of the boundaries and the antisymmetry between the forward and backward propagations of phase angles Thus, we haveThe full spectrum of eigenvalues for phase stability is solved based on Eq. (52) for each mode identified by the integer . The stability criteria are determined by the parametric gain as explained previously. 4.Results and DiscussionWe aim to investigate the amplitude and phase stabilities under the GVD and saturable absorber effects. Our ultimate goal is to tailor these effects to design a QCL for MIR pulse generation, so we vary the GVD and saturable absorber strength within a certain range by referring to the parameters provided in the literature8,10 to examine the interaction between the GVD and the saturable absorber. The saturable absorber strength of the QCL structure (wafer No. 3251) emitting at 8.47 μm is between when the active region width is in the range of 3–7.5 μm.10 The saturable absorber strength is estimated based on .10 We take this structure as our simulation prototype and set the variation range of the saturable absorber strength to be . The waveguide structures of the QCL in Refs. 8 and 10 (the waveguide structure of Ref. 10 is detailed in Ref. 18) are similar. They are both grown by metal organic vapor-phase epitaxy (MOVPE) and made by an InGaAs/InAlAs core and highly Fe-doped InP cladding layers. Thus, for our simulation, we can adopt the GVD coefficient of the structure in Ref. 8 as the baseline of our GVD variation. As reported in Ref. 8, the measurement of a QCL with an InGaAs/InAlAs active region shows an anomalous GVD coefficient .8 We set the variation range of the GVD coefficient to be . For other parameters, we follow the parameters provided for the Fabry–Perot cavity in Ref. 10. We studied the amplitude and phase instabilities with both the GVD and saturable absorber existing in the cavity under various pumping strengths. Results are presented in Fig. 1 for amplitude instability and in Fig. 2 for phase instability. We want to note that the line type and color assignment shown in the insert of Fig. 1(a) also apply to all other figures. In each case, the stability is demonstrated by the parametric gain versus detuning frequency. For reference, in each figure, we also present the cases when the GVD or saturable absorber is absent, i.e., or . In our simulation procedure, we found that the amplitude (or phase instability) responds almost indifferently to the strength of the GVD when has the range of , which is a reasonable range for the QCLs (Refs. 8 and 17). Thus, we only show the results with to represent the cases with the GVD effect. Fig. 1Amplitude stability with the existence of GVD and saturable absorber effects under different pumping strengths : (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) .  Fig. 2Phase instability with the existence of GVD and saturable absorber effects under different pumping strengths : (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) .  The amplitude instability without the GVD effect exhibits as that of an RNGH-type instability. From Fig. 1, it can be found that, under each pumping level, the presence of the GVD alters the influence of the saturable absorber on the amplitude instability. That is, an increase in the saturable absorber strength can drive the amplitude to be more stable when the GVD is present. Inversely, a stronger saturable absorber boosts the instability by lowering the instability threshold when the GVD is absent.10,12 Thus, the lasing cavity with a stronger saturable absorber effect is less affected by the presence of the GVD. The interaction between the GVD and the saturable absorber on the amplitude instability is also affected by the pumping strength . Figure 1(a) tells that, under low pumping strength, the GVD tends to destabilize the amplitude and flattens the parametric gain curve throughout all frequency modes. When the pumping strength gets stronger, as shown in Figs. 1(b), 1(c), and 1(d), the effect of the GVD can be suppressed by the saturable absorber effect. Hence, the instability without the GVD resembles that of the instability with the GVD, especially for the frequency portion that is closely around the central frequency. Apparently, to achieve such suppression, the weaker the saturable absorber is, the higher is the pumping strength needed. This is because of the fact that the suppression is related to the nonlinear portion of the loss . We notice that, in Figs. 1(c) and 1(d), for the case with the highest saturable absorber strength under study, the symmetry of the gain spectrum about the central frequency is broken, which is mathematically caused by the emergence of an imaginary part in the steady-state solution. The phase instability is of a single-mode nature. The GVD has a lesser effect on the phase instability than it does on amplitude instability, especially, the GVD effect is almost suppressed at a higher pumping level. At a lower pumping level, the destabilization of the phase by the GVD only happens at frequencies that are away from the central frequency. 5.ConclusionsWe present an analysis procedure on the amplitude and phase instabilities of MIR QCLs with the presence of GVD and saturable absorber effects in the lasing cavity. The significance of this work is in accounting for the GVD effect, whose presence in MIR QCLs has been substantiated, in the discussion of QCL instability mechanisms. Stability analysis was performed through the linearization of dynamic equations based on the Maxwell–Bloch formalism. Because of the second-order differential term brought by the GVD, the quadratic eigenvalue problem results from the linearization and it is treated by a degeneration technique. The instability mechanisms are decoupled into amplitude and phase domains through the symmetry or antisymmetry propagation of fields along the cavity. Simulation results show that the effect of the GVD on the stability of QCLs is largely dependent on the saturable absorber and pumping strength. The GVD could significantly destabilize the QCL pulse amplitude under a lower pumping level and weaker saturable absorber strength. With the increase of pumping and saturable absorber strength, the GVD effect could be suppressed. The GVD has only a slight effect on the phase instability, and the effect decreases as the frequency approaches the central frequency. The results obtained from this research will contribute to our further investigation on the topic of soliton dynamics of QCLs for MIR pulse generation. AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) by Grant No. ECCS-1232273. The authors would like to thank Dr. Qijie Wang in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, for helpful discussions. ReferencesC. Gmachlet al.,

“Recent progress in quantum cascade lasers and applications,”

Rep. Prog. Phys., 64

(11), 1533

–1601

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/64/11/204 RPPHAG 0034-4885 Google Scholar

Y. YaoA. J. HoffmanC. Gmachl,

“Mid-infrared quantum-cascade lasers,”

Nat. Photon., 6

(7), 432

–439

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2012.143 1749-4885 Google Scholar

A. A. KosterevF. K. Tittle,

“Chemical sensors based on quantum-cascade lasers,”

IEEE J. Quantum Electron., 38

(6), 582

–591

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JQE.2002.1005408 IEJQA7 0018-9197 Google Scholar

R. Paiellaet al.,

“Self-mode-locking of quantum cacade lasers with giant ultrafast optical nonlinearities,”

Science, 290

(5497), 1739

–1742

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5497.1739 SCIEAS 0036-8075 Google Scholar

R. Paiellaet al.,

“High-frequency modulation without the relaxation oscillation resonance in quantum cascade lasers,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 79

(16), 2526

–2528

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1411982 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

R. C. IottiF. Rossi,

“Nature of charge transport in quantum-cascade laser,”

Phys. Rev. Lett., 87

(14), 146603

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.146603 PRLTAO 0031-9007 Google Scholar

J. BaiD. S. Citrin,

“Intracavity nonlinearities in quantum-cascade lasers,”

J. Appl. Phys., 106

(3), 031101

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3180960 JAPIAU 0021-8979 Google Scholar

H. Choiet al.,

“Time-domain upconversion measurements of group-velocity dispersion in quantum-cascade lasers,”

Opt. Express, 15

(24), 15898

–15907

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.15.015898 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

C. Y. Wanget al.,

“Coherent instabilities in a semiconductor laser with fast gain recovery,”

Phys. Rev. A, 75

(3), 031802(R)

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.75.031802 PLRAAN 1050-2947 Google Scholar

A. Gordonet al.,

“Multimode regimes in quantum cascade lasers: from coherent instabilities to spatial hole burning,”

Phys. Rev. A, 77

(5), 053804

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.77.053804 PLRAAN 1050-2947 Google Scholar

J. Bai,

“Effect of self-phase modulation on the instabilities of quantum-cascade lasers,”

J. Nanophoton., 4

(1), 043519

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3518086 JNOACQ 1934-2608 Google Scholar

J. Bai,

“Phase instability and amplitude instability of quantum-cascade lasers with Fabry-Perot cavity,”

IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol., 11

(2), 292

–297

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNANO.2011.2169455 ITNECU 1536-125X Google Scholar

H. RiskenK. Nummedal,

“Self-pulsing in lasers,”

J. Appl. Phys., 39

(10), 4662

–4672

(1968). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1655817 JAPIAU 0021-8979 Google Scholar

R. GrahamH. Haken,

“Quantum theory of light propagation in a fluctuating laser-active medium,”

Z. Phys. A, 213

(5), 420

–450

(1968). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01405384 ZEPYAA 0044-3328 Google Scholar

G. P. Agrawal, Nonlinear Fiber Optics, 3rd ed.Academic Press, San Diego, California

(2001). Google Scholar

A. Hugiet al.,

“Mid-infrared frequency comb based on a quantum cascade laser,”

Nature, 492

(7428), 229

–233

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11620 NATUAS 0028-0836 Google Scholar

M. A. TalukderC. R. Menyuk,

“Self-induced transparency modelocking of quantum-cascade lasers in the presence of saturable nonlinearity and group velocity dispersion,”

Opt. Express, 18

(6), 5639

–5653

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.18.005639 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

L. Diehlet al.,

“High-power quantum cascade lasers grown by low-pressure metal organic vapor-phase epitaxy operating in continuous wave above 400 K,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 88

(20), 201115

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2203964 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

Biography Jing Bai is an associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD). She received her PhD degree and MSc degree in electrical and computer engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology in 2007 and 2003, respectively. She also earned the MEng degree in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, in 1999 and the BEng degree in Tsinghua University, China, in 1996, both in mechanical engineering. Her studies focus on theoretical investigations on intracavity nonlinearities and dynamic behaviors of nanoscale optoelectronic structures. She also extends her research interests to the biomedical applications of optoelectronic technologies.  Debao Zhou joined the Faculty of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at UMD in January 2009. Prior to that, he was a McKnight professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at UMD. From January 2005 to January 2008, he was with Georgia Tech Research Institute as a postdoctoral fellow. He received his PhD degree in mechanical and production engineering from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, in 2004. He earned his MEng degree and BEng degree from Tsinghua University, China, both in mechanical engineering. His research interests include system dynamics and control, distributed force sensor design for biomedical applications, and image processing techniques for intelligent transportation systems. |